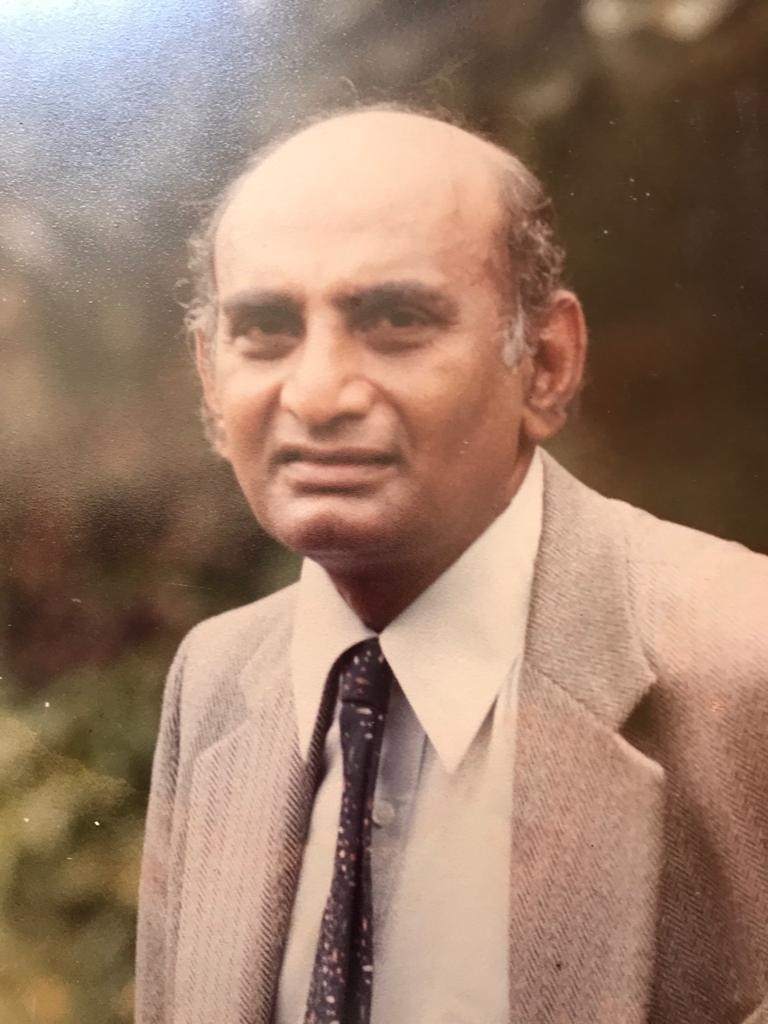

Professor David (Devendranathan) Chanmugam – an Eulogy

- Dr D S Kumararatne

- Sep 20, 2021

- 10 min read

Tributes from two of his distinguished students.

We are privileged to be able to publish obituaries from two people who knew the late Professor Chanmugam very well. Their tributes are “straight from the heart” and very personal.

The first is from Dr. D. S. Kumararatne, Consultant Immunologist and Director of Cambridge Immunology at the Addenbrooke’s Hospital. The second is from Dr. Upali Banagala, Consultant in Orthopaedic Surgery at the National Hospital in Colombo

This tribute was first published by Professor Sanjiva Wijesinghe in his personal website and we publish it here with his consent (which he was delighted to provide).

When one approaches the composition of an eulogy for a former teacher, the process is usually influenced by sorrow. However, in the case of writing an eulogy for my former teacher and mentor, Dr. David (Devendranathan) Chanmugam, I do it with a sense of elation, from having had the great good fortune of knowing and coming under the influence of a gentle, kind, and good man who was a consummate physician, and who embodied the description that a good doctor ‘cures sometimes, relieves often, but comforts always’.

I entered medical school in 1967 and commenced clinical studies in 1969, the same year Dr. Chanmugam joined the faculty at the Department of Medicine of the University of Ceylon (Colombo) as a senior lecturer. I have no recollection of being taught by Dr. Chanmugam when I was a medical undergraduate. I first came under his influence when I joined his clinical firm as an intern medical house officer in 1973.

My first house job was working in the professorial surgical unit at the Colombo General Hospital for Professor RA Navaratne as well as with Dr. Sheriffdeen and Dr. Gerry Jayasekera, who were newly appointed consultant surgeons. I really enjoyed this time – even though I was a rookie doctor, I was treated as an individual whose opinions counted. Therefore, it came as a real shock working in my next house job in the professorial medical unit, headed by Professor Kumaradasa Rajasuriya – where house officers were meant to be seen and not heard, with the rest of the team scrambling to please him and not fall into disgrace with the great man.

At this time, the female ward in the professorial medical unit was under the supervision of the senior lecturer Dr. Chanmugam, and the intermediate tier of doctors did not bother to get involved with the patients under his care, presumably as there were scant brownie points to be gained from the bid chief, Prof Rajasuriya! My three months working as a houseman directly under the supervision of Dr. Chanmugam was a very rewarding and pleasant experience. Rewarding, because Dr. Chanmugam practiced scientific, evidence-based medicine before this concept was fashionable. He was a kind and caring doctor – but his clinical practice was governed by intellectual rigor and the highest ethical standards. For example, he would not empirically commit a patient with fever of unknown origin to a long trial of anti-tuberculous therapy without attempting further steps to get objective evidence of this diagnosis. I learned from him that before committing patients at that time to a year or even two of combined antibiotic therapy, if one performed a needle biopsy of the liver one would often identify caseating granulomata which confirmed the diagnosis of tuberculosis.

Young adults presenting with enlarged cervical lymph nodes were not uncommon. Often, Tuberculosis of the cervical lymph node was the underlying diagnosis – but Dr. Chanmugam always undertook a cervical lymph node biopsy under local anesthesia to get objective evidence of this diagnosis before launching into treatment. After watching him, I became quite adept at doing this myself.

Due to his background in haematology, most patients with haematological malignancies who came into the Professional unit came under his care. In the early 1970s, in a resource limited country, treatment of these patients was not for the fainthearted. Dr. Chanmugam, however, did his utmost for these patients and was unfailingly kind and supportive to these individuals with a life limiting illness.

Why was working as a houseman for Dr. Chanmugam a pleasant experience? Because even though you were a junior doctor, you were treated with courtesy and your opinions were respected. A striking example: an unmarried 13-year-old female was admitted during our emergency intake with abdominal pain and suspected of having appendicitis. I was the first person to review her as the house officer on call. Based on theoretical information I learned from that classic A Textbook of Gynecology by Jeffcoate, I suspected that this young lady’s symptoms were due to a ruptured ectopic pregnancy (a pregnancy implanted outside the womb in a thin tube leading to the womb. This was not an easy possibility to manage in a relatively conservative Asian country. However, I took my courage in my hands and informed Dr. Chanmugam. He listened to my reasoning and my concerns seriously and sought a gynecological consultant’s opinion. The patient indeed had a ruptured ectopic pregnancy and made a good recovery after surgery. This action probably saved her life as well. At that time, there were no rapid pregnancy tests. I vaguely remember that you had to inject the patient’s urine into a female toad and observe whether it laid frog spawn to diagnose pregnancy!!

Dr. Chanmugam was a private person and a very modest person, so I did not know much about his career or accomplishments (in contrast to the usual Sri-Lankan habit of never hiding one’s light under a bushel). However, I did some research (the results of which were not easy to find during the pre-Internet era) and recognised that he had worked with two pioneers of leukemia chemotherapy, RS Schwartz, and W. Damashek. These American pioneers utilised the information gleaned from the use of Nitrogen mustard as a poison gas during the First World War, to employ derivatives like cyclophosphamide to treat haematological malignancies.

I had never observed which make of car Dr. Chanmugam owned – because (unlike all the other consultants at the Colombo General Hospital) he rode to work on a bicycle! He never spoke ill of anybody or engaged in gossip – the latter being a common occurrence within the Professional medical unit at that time.

Dr. Chanmugam was the only one of my clinical trainers who perceived that I did not wish to pursue a conventional career pathway, where one worked up the medical hierarchy – senior house officer, registrar and senior registrar with a clinical firm, completing postgraduate fellowships on the way. Instead, I wished to pursue a research pathway before completing clinical training – and that again in a discipline that had hitherto not been followed in Sri-Lanka, namely clinical immunology. Dr. Chanmugam wrote on my behalf, to academic immunologists in Boston to help me secure a research fellowship. Although I did not follow these openings and went to Oxford instead, I greatly appreciated this act of generous mentorship. While I was ‘marking time’ at the University Department of Pathology at the medical school till it was time for me to leave for overseas, he realised that I was getting bored due to the lack of intellectual stimulation. He therefore directed me to undertake a research project investigating the activation of the bactericidal oxidative metabolic pathway within neutrophils. This had recently been described, and he suggested that I investigate this as a marker of identifying active bacterial infections in patients. This was a test I could easily carry out in practice, and Dr. Chanmugam bought me the reagents necessary to do these experiments.

As Dr. Chanmugam was reserved about his personal circumstances, I did not have enough information to flesh out the man. When I agreed to write this appreciation, I expected to get the relevant information by searching online. Google was entirely silent about him, and all I could find out was the address that he resided at in Washington DC, and that at one time he had been resident in Florida, probably living with his son or daughter-in-law.

I was very fortunate that his elder brother, Chandi, kindly indulged me and provided the following information about Devendranathan (David).

He was the third of five children of W.R. Chanmugam (who was the first Sri-Lankan to be appointed government analyst) and his wife, Rasu. He had his primary education at St Thomas’s preparatory school, Colombo until 1941, when there was an imminent threat of a Japanese invasion of Sri-Lanka. The Chanmugam clan moved all their children who were under the age of 15 to the north of the island; David and his brother attended Jaffna Central College (where their grandfather was headmaster) as boarders. In 1945 at the end of the war, David joined the premier government school, Royal College in Colombo – from where he gained admission to the University of Ceylon medical faculty.

I have been unable to obtain information about David’s undergraduate career, except for an entry in the Colombo medical school centenary souvenir publication that he was awarded the Myelopulle Silver Medal for Materia Medica and Pharmacology in 1952. He qualified as a doctor in 1954, and then proceeded to be a final year student at King’s College Hospital Medical School in London, achieving another MBBS from the University of London in 1955. He completed his internship and junior medical appointments in various hospitals in London with a final stint in oncology at the Royal Marsden Hospital.

The next stage in his career is a testament that his academic and clinical potential were highly regarded, as he held two prestigious fellowships in haematology – first at the Albert Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia, and subsequently at the most prestigious New England Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts, under the supervision of the famous giants in the discipline, Dr. W. Damashek and Dr. R.S. Schwartz. During this period, he was the first author of several publications in the premier tier of medical journals, including the Journal of Experimental Medicine and the New England Journal of Medicine.

At the end of his hematology fellowships, he returned to Sri Lanka and was appointed consultant physician at the General Hospital in Kandy in 1965. Four years later he became a senior lecturer in medicine at the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Ceylon (Colombo). The fact that his elevation to the post of Professor of Medicine in Colombo only in 1978 is probably a reflection of the internal politics in the faculty at that time.

In his curriculum vitae, compiled around 1986, he cited two of the most eminent UK physicians as referees – namely, Sir John Badenoch of Oxford and Professor Oliver Wrong of University College London. I could not seek their memories of Dr. Chanmugam, as they are no longer alive.

After the unsettling political and social developments in Sri-Lanka in 1983 he retired in 1986 and moved to the USA, primarily to ensure the safety of his five sons and also to provide them with the opportunity for tertiary education. David practiced medicine in the USA until his final retirement in 2004. He had begun to exhibit signs of Alzheimer’s Disease and so returned to Colombo in 2014 where he was cared for at a nursing home from 2015 until he passed away on 8 June 2021.

I learned from his brother that David was an enthusiastic and excellent sportsman, playing cricket tennis (his favorite game) and hockey. His transport was a bicycle which he used to commute about town, attend church, and travel to the tennis courts.

From my personal observations and those of his colleagues, his patients, and his family, Devendranathan Chanmugam was a simple man, a modest man, a kind and caring man – and a skilled physician who strove to practice evidence-based, scientific medicine. His clinical skill was leavened by compassion and high ethical standards. He was always polite and calm . He was never flustered, never spoke ill of anybody, and did not engage in gossip. Despite having to care for a relatively large family, he did not practice private medicine, which was unusual among the physicians working at the General Hospital in Colombo during my time.

Of David Chanmugam we can say in the words of Shakespear His life was gentle, and the elements. So mix‘d in him that Nature might stand up. And say to all the world, “This was a man!”

I might add that this poem, The Measure of a Man (attributed initially to Albert Schweitzer, but this was later disputed and so is now attributed to an anonymous poet) encapsulates, who Dr. David Chanmugam was:

Not – How did he die? But – How did he live? Not – What did he gain? But – What did he give? These are the things that measure the worth Of a man as a man, regardless of birth. Not – What was his station? But – had he a heart? And – How did he play his God-given part? Was he ever ready with a word of good cheer? To bring back a smile, to banish a tear? Not – What was his church? Not – What was his creed? But – Had he befriended those really in need?

Not – What did the sketch in the newspaper say? But – How many were sorry when he passed away?

These are the things that measure the worth Of a man as a man, regardless of birth.

A delightful, sincere and very personal tribute from Upali.

I worked with Prof Chanmugam as his intern from October 1978 to March 1979

He use to come to the by 7 am

I used come to the ward before that with out breakfast and my wife ( girlfriend at that time ) Champa use to bring breakfast from home ,I take the breakfast in the ward

He has instructed the ward staff not to inform me until I finish breakfast that he has come and he starts the ward round alone.

He was my second father during this time

He was one of the very few consultants who took great care of his patients .since his specialty was Haematology he took great care of them .

He made Reg sure his Patients can be looked after well at home before discharging them.

If not he will keep them in the ward till circumstances are suitable.

He was so nice to his house officers Spoke to them very kindly. After I left him the following year I used to visit that ward when Champa was there and he welcomed me in his ward. Always spoke to me if he saw me.It was very pleasant to meet him.

During her internship Champa delivered and he has told her not to come to ward early but to settle the baby first .He told her that he comes early to drop his children to school and it is enough if she comes at 8.00 a. m. This type of understanding Consultants are rarely found now.

He never did Private Practice and took great care of all patients under him in the ward and OPD

He was a great Academic Clinician which you rarely come across now.

These are some of my thoughts

Upali Banagala

Comments